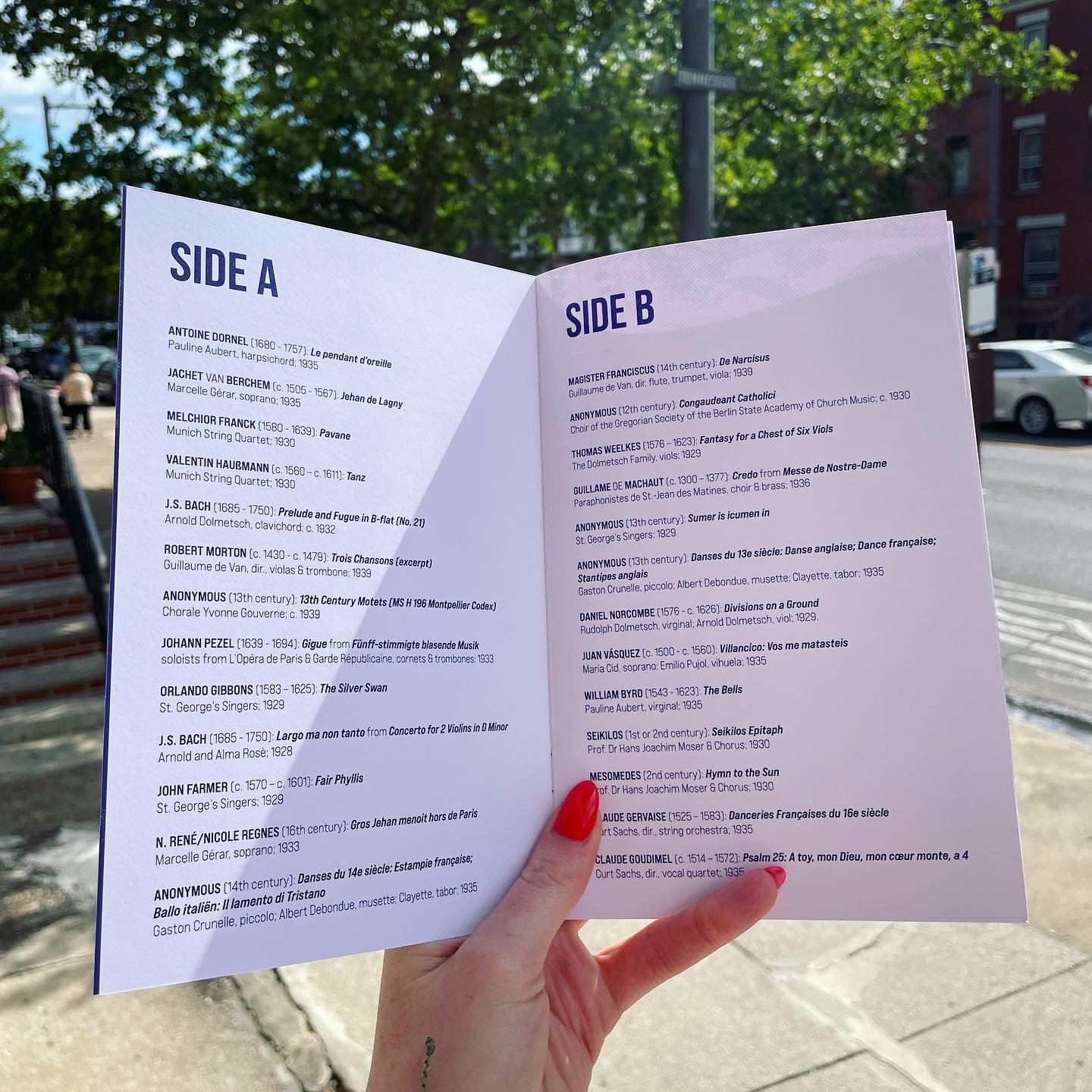

SEMIBEGUN 001: EARLY RECORDINGS OF EARLY MUSIC 1928 - 1939

Air/Release Date: June 8, 2022

A

Antoine Dornel (1680 - 1757): Le pendant d'oreille

Pauline Aubert, harpsichord; 1935Jachet van Berchem (c. 1505 - 1567): Jehan de Lagny

Marcelle Gérar, soprano; 1935Melchior Franck (1580 - 1639): Pavane

Munich String Quartet; 1930Valentin Haußmann (c. 1560 – c. 1611): Tanz

Munich String Quartet; 1930J.S. Bach (1685 - 1750): Prelude and Fugue in B-flat (No. 21)

Arnold Dolmetsch, clavichord; c. 1932Robert Morton (c. 1430 - c. 1479): Trois Chansons (excerpt)

Guillaume de Van, dir., violas & trombone; 1939Anonymous (13th century): 13th Century Motets, MS H 196 Montpellier

Chorale Yvonne Gouverne; c. 1939Johann Pezel (1639 - 1694): Gigue from Fünff-stimmigte blasende Musik

soloists from L'Opéra de Paris & Garde Républicaine, cornets & trombones; 1933Orlando Gibbons (1583 – 1625): The Silver Swan

St. George's Singers; 1929J.S. Bach: II. Largo ma non tanto from Concerto for 2 Violins in D Minor

Arnold and Alma Rosè; 1928John Farmer (c. 1570 – c. 1601): Fair Phyllis

St. George's Singers; 1929N. René/Nicole Regnes (16th century): Gros Jehan menoit hors de Paris

Marcelle Gérar (soprano); 1933Anonymous (14th century): Danses du 14e siècle: Estampie française; Ballo italiën: Il lamento di Tristano

Gaston Crunelle, piccolo; Albert Debondue, musette; Clayette, tabor; 1935

B

Magister Franciscus (14th century): De Narcisus

Guillaume de Van, dir., flute, trumpet, viola; 1939Anonymous (12th century): Congaudeant Catholici

Choir of the Gregorian Society of the Berlin State Academy of Church and School Music; c. 1930Thomas Weelkes (1576 – 1623): Fantasy for a Chest of Six Viols

The Dolmetsch Family, viols; 1929Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300 – 1377): Credo from Messe de Nostre-Dame

Paraphonistes de St.-Jean des Matines, choir & brass; 1936Anonymous (13th century): Sumer is icumen in

St. George's Singers; 1929Anonymous (13th century): Danses du 13e siècle: Danse anglaise; Dance française; Stantipes anglais

Gaston Crunelle, piccolo; Albert Debondue, musette; Clayette, tabor; 1935Daniel Norcombe (1576 - c. 1626): Divisions on a Ground

Rudolph Dolmetsch, virginal; Arnold Dolmetsch, viol; 1929.Juan Vásquez (c. 1500 - c. 1560): Villancico: Vos me matasteis

Maria Cid, soprano; Emilio Pujol, vihuela; 1935William Byrd (1543 - 1623): The Bells

Pauline Aubert, virginal; 1935Seikilos (1st or 2nd century): Seikilos Epitaph (Skolion of Seikilos)

Prof. Dr Hans Joachim Moser & Chorus; 1930Mesomedes (2nd century): Hymn to the Sun

Prof. Dr Hans Joachim Moser & Chorus; 1930Claude Gervaise (1525 – 1583): Allemande (Danceries Françaises du 16e siècle)

Curt Sachs, dir., string orchestra; 1935Claude Goudimel (c. 1514 – 1572): Psalm 25, A toy, mon Dieu, mon cœur monte, a 4

Curt Sachs, dir., vocal quartet; 1935

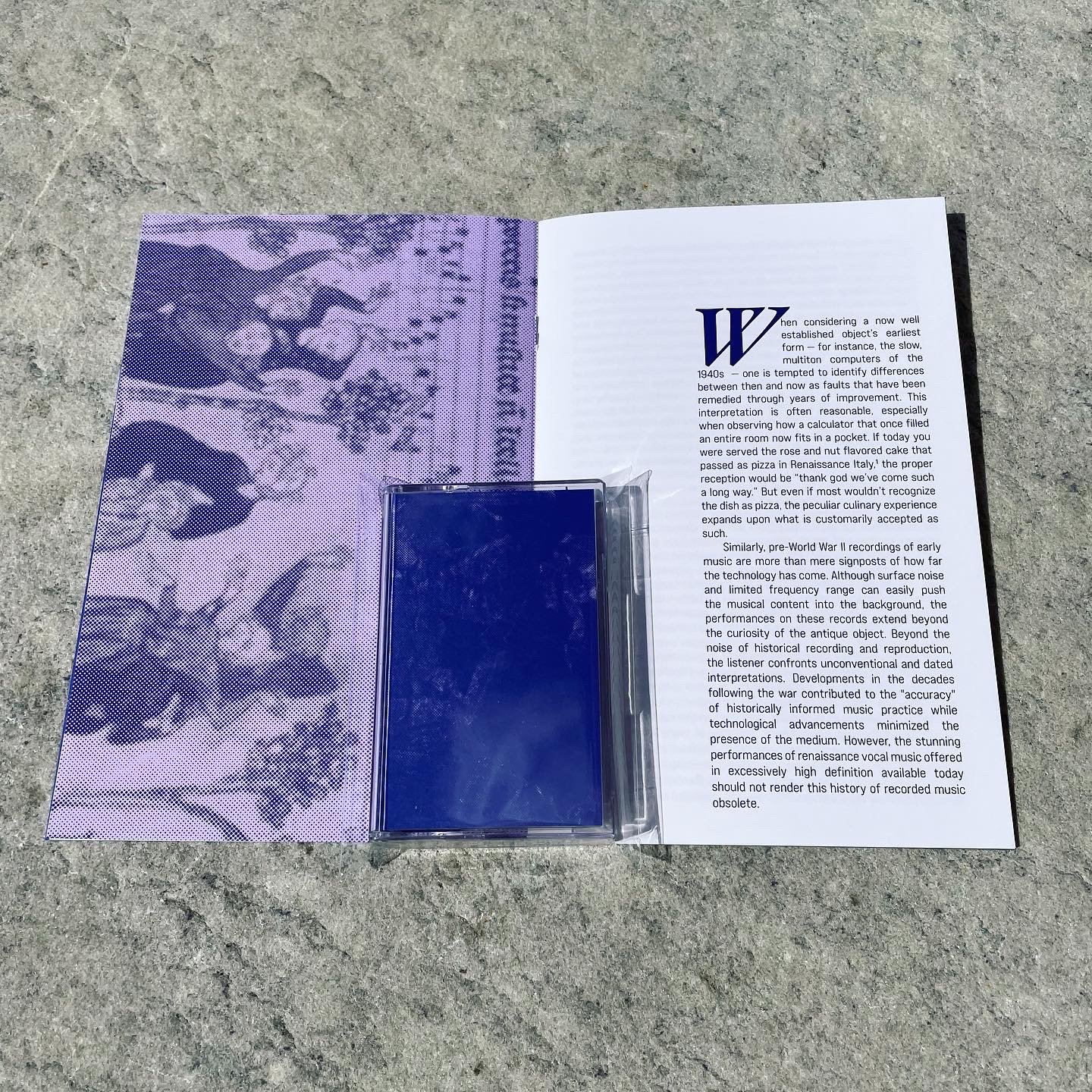

Cassette + booklet available for purchase, please email.

When considering a now well established object’s earliest form – for instance, the slow, multiton computers of the 1940s – it’s tempting to focus on differences between contemporary or later versions solely as faults that have been remedied through years of improvement. Especially when observing how a calculator that once filled an entire room now fits in a pocket, the improvements aren’t restricted to design and efficiency, but have profound cultural consequences. If today you were served the rose and nut flavored cake that passed as pizza in Renaissance Italy,[1] you would properly respond “thank god we’ve come such a long way.” Unrecognizable to most, the peculiar (yet probably very delicious) dish expands upon what we customarily accept as pizza. When taken into historical context, this unfamiliar pie-cake challenges our conceptions of what pizza is and pushes the limits of what it can be. By dismissing a linear narrative of progress and notions of primitivism, pre-canonized forms, like our early pizza, provide invigorating perspectives for experimentation and alternative narratives to recontextualize contemporary forms.

Similarly, the early music recorded before World War II offers more than simple indications of how far the technology has come. Although surface noise and limited frequency range can easily push the musical content into the background, the performances on these records extend beyond the curiosity of the antique object. Beyond the noise and constrained fidelity of historical recording and reproduction, the contemporary listener confronts unconventional and by today's standard's outdated interpretations of historical music. Developments in the decades following the war contributed to the "accuracy" of historically informed music practice while technological advancements minimized the presence of the medium. However, the stunning performances of renaissance vocal music available in excessively high definition today should not render these early recordings obsolete. These recordings comprise a particular chapter in the recorded history of music, one that brings its own conceptions of "authenticity" to the table.

The period of "early music" commonly comprises the European Middle Ages to the Baroque era (and sometimes includes ancient music), over a thousand years, and covers greatly varying styles across centuries, composers, cultures, religions, and purposes. Simply, early music consists of myriad early musics. Similar in spirit to much twentieth and twenty-first century concert music, the distinctiveness of early music may seem convention-defying to the conservative listener: angular form, metrical ambiguity, peculiar timbres, and expectation-thwarting harmonic movement. Musicologist Thomas Forrest Kelley credits the appeal of earlier repertories with their ability to provide a “means of connecting with worlds so different from our own that they give us reason to question our assumptions about how music works, what it does, and what it should sound like.”[2] A visual analogue like the medieval paintings that feature a flattened Madonna holding an elderly baby Jesus or bizarre marginalia depicting such delights as creatures with trumpets sticking out of their rear ends, similarly confronts the viewer with fantastical abstractions, eccentric displays of piety, and fascinating intersections of culture, class, aesthetics, and religious spectacle which together verge on uncanny. Modern and contemporary music shares a similar questioning and confrontational spirit, which likely explains the overlap in early and new musical interests for performers, audiences, and composers (can program notes for a new piece of sound art or electro-acoustic music be complete without a little bit of questioning and confrontation with the nature of sound in contemporary culture?). Kelley’s remark can also apply to repertories of early recording, where the grain of the phonographic media amplifies a perceived otherworldliness in late 19th/early 20th century music. The amplification compounds at the intersection of early music with early recording and reproduction technology.

This mix contains music recorded between 1928 and 1939, with content spanning Ancient Greek to Baroque periods. Here, different ideas of “early” intermingle with one another: early music, early recording technology, and early historical performance practice. All of the tunes were transferred from 78-rpm shellac discs by a variety of sources on the Internet Archive. Anyone who has taken a survey course in Western music history will likely recognize some of the music. Almost a century later, textbooks like the Norton Anthology of Western Music still include classics like Sumer is icumen in and Seikilos Epitaph (Skolion of Seikilos in Parlophone’s 2000 Years of Music collection), albeit with updated scholarship. Likewise, the selected thirteenth and fourteenth century dances are still quite popular with professional and amateur performers as are the English madrigals The Silver Swan and Fair Phyllis. Deeper cuts emerge as well, like Gros Jehan menoit hors de Paris by an N. René. The earliest works date to the first few centuries of the common era, and the latest almost hug the beginning of the Classical period.

The majority of the selections come from three anthologies of historical music: 2000 Years of Music, L’Anthologie Sonore, and Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye. The music directors of these records, some of whom were musicologists responsible for rediscovering repertoire and developing its performance practice, presented authoritative performances for the time.[3] German musicologist Curt Sachs directed two of the earliest historic anthologies of early music: 2000 Years of Music, produced through the German label Parlophone in 1930 and L’Anthologie Sonore, founded a few years later after leaving Germany for France. Both collections prioritized Sachs’ principles to showcase “ten centuries of music,” “absolute musical authenticity,” and “musical quality” in terms of curation that satisfies musicological and “our modern human sensitivity.”[4] The accompanying textbook for 2000 Years of Music offers peculiar perspectives on the early music canon, for instance this claim about the groundbreaking character of opera: “For the first time in its history, music was called upon to express human emotions where before it had been content to remain absolute. Such music required naturally a new form and that form was Opera.”[5] Although the text occasionally dips into questionable territory, most of the recordings in the twelve disc collection are quite lovely even if the interpretations also sound dated.

Columbia worked with Percy Scholes, writer of the first edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, as the artistic director for the series Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye. Featured on many of the Columbia recordings, the Dolmetsch family performed on clavichord, virginal, harpsichord, and viols when piano and modern strings would have been considered acceptable substitutions to many. The heavy, affected string orchestra of violins, violas, gambas, basses directed by Curt Sachs on Claude Gervaise's Allemande (Danceries Françaises du 16e siècle) indicates this attention to instrumentation may not have always been viable. Many of the harmonic subtleties inherent to the viol are replaced with a glassier sound in Weelke's Fantasy for a Chest of Six Viols, performed by the Dolmetsch Family, suggesting they recorded poorly (or were poorly recorded). Entirely absent from most of these performances is the now ubiquitous practice of straight tone, or singing without vibrato. St. George’s Singers vibrate throughout the two madrigals Fair Phyllis and The Silver Swan. This tendency is not restricted to the voice: the string quartet’s punchiness doused in heavy vibrato on Melchior Franck’s Pavane more appropriately suits a Fritz Kreisler piece than a dance from the early 1600s. A reviewer in 1932 may have agreed with this assessment when he describes the recording as “pleasing and surprisingly fresh.”[6] Sharing a similar level of outmoded intensity, the ensemble performing Guillaume de Machaut’s beautiful 14th century Messe de Nostre-Dame belt in a style not unlike American shape note singing. Today, such performances would more likely be heard in student and amateur ensembles than on professional releases.

Some of the more curious performances come from the label L’Oiseau Lyre, a passion project led by socialite Louise Hanson-Dyer that began producing records in 1938. Alongside a crew of young and seasoned scholars, she recorded editions from the label’s publishing arm Éditions de l’Oiseau-Lyre, including selections from the 13th-century Montpellier Codex. The motet from this codex of medieval polyphony features delicate high voices employing narrow vibrato and, perhaps most interestingly, the interjection of an unedited reference pitch given by a piano during a brief pause at around the two-third mark. The far more clumsy performance of Magister Franciscus’s De Narcisus by a jarringly out-of-tune and inspiringly lifeless ensemble of flute, viola, and trumpet paints a certain rugged early twentieth century approach. For even the uninitiated listener, the decision to cut something like this to tape seems questionable. A poor record was not always just the result of inauthenticity or poor artistic direction. Technology also hindered the process.

The starting year of this mix’s range, 1928, roughly corresponds to a significant point in the history of recording: the early years of the electrical recording era. The acoustic era, the period between 1877 and 1925, effectively ended when the widespread adoption of microphones ushered in the electrical era.[7] Almost all phonographs of the acoustic era operated without electricity, and instead captured and reproduced sound mechanically. Electrically amplified recording increased the ease of the capture process and the quality of sound.[8] The flexibility afforded by an electrically amplified microphone system allowed the capture sounds around a wide area, ending the practice of hellishly cramped recording sessions around an acoustic horn. This led to more comfortable working conditions and an expansion of how and what music ensembles could practically record. Increases in captured frequency range also expanded this practicality. Acoustic recording could only reproduce sound within a frequency range of 168 to 2,000 Hz (the human ear can hear, ideally, between 20 and 20,000 Hz).[9] This limitation accounts for diminished speech intelligibility on wax cylinder recordings. The presence of important timbral information that aids interpretation, for instance the sibilance sounds of ‘f,’ ‘s,’ and ‘th,’ decreases in such a limited frequency space. Particularly high voices like sopranos have a pallid, wraithy quality due to this timbral flattening, audible in the highest vocal part of Fair Phyllis and the top of the song’s range in Jehan de Lagny. Although out of the scope of this mix, the rare turn-of-the-century recordings of castrato Alessandro Moreschi demonstrate similar acoustic qualities.

The audio industry was certainly aware of the technological limitations, as were critics and consumers. Overwhelming negative reviews of sound film recordings by Metropolitan Opera coloratura soprano Marion Talley described her vocal performance as “intolerably piercing shrieks,” ending her screen career as an unfortunate consequence of being out of reproducible range.[10] In an example of misogyny in early twentieth century acoustics, a Bell Labs engineer goes further to extend the issue of high voice intelligibility to a general acoustic diagnosis of women’s speech being “more difficult to interpret than man’s… due in part to the fact that woman’s speech has one-half as many tone’s as man’s, so that the membrane of hearing is not disturbed in as many places.”[11] While higher voices do suffer more from a lower frequency range of reproduction, which certainly was the case in 1928, this is generally a non-issue in everyday speech for people with average hearing. Wanting to spin the situation, Edison instead praises the early phonograph’s low fidelity for its ability to eliminate non-essential material and vocal imperfections, even improving or correcting these “mutilations” by passage through the mechanism.[12] While the machine would reduce some potentially irritating vocal qualities like a speaker’s harsh sibilance, that lack would also reduce clarity in a practical application like transcription.

Despite technological shortcomings, marketing for the early phonograph focused on its purpose as a device to record speech. It was even commonly referred to as a “talking machine.” Sound recording technology emerged alongside a revolution in business management which sought to increase efficiency through technology and reorganization.[13] Professional managers oversaw employees using new technologies like typewriters and dictation phonographs in newly compartmentalized departments like accounting and communications. As the “scientifically managed office” came into vogue, gender roles in the office began to shift. Men, who previously worked as secretaries, became managers of a primarily female fleet of technologically proficient secretaries. As more women entered the workforce at the beginning of the twentieth century, advertising began reflecting the contemporary workplace with images of men dictating onto a phonograph cylinder while women transcribe them.[14] Edison had non-entertainment applications of the technology on his mind from the beginning. In an article from 1878 titled “The Phonograph and Its Future,” Edison emphasizes the Phonograph’s application in communication and dictation well over its potential as a device for entertainment or education. He first lists dictation, then audio books for use in “asylums of the blind, hospitals, the sick-chamber, or even with great profit and amusement by the lady or gentleman whose eyes and hands may be otherwise employed.”[15] With the two- and later four-minute run time of wax cylinders, a recording of even a small novel would require quite a lot of storage space and constant cylinder loading. A work like Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, with an audio length of about thirty-five hours, would require over a thousand two-minute cylinders. After books Edison lists education purposes primarily for children, and then music, praising the phonograph’s ability to reproduce a song with “marvelous accuracy and power.”[16] As music proved more complicated than speech to record, over a decade would pass before the first commercial recordings in 1889.

Decades later, the jump to electrical amplification in the mid 1920s increased the captured frequency range to 5,000 Hz (down to 100 Hz on the lower end), and again up to 8,000 Hz by 1934. Because microphones could now capture a greater dynamic range while offering more spatial flexibility than performance into a horn allowed, recorded music could achieve more levels of depth and expressivity. The limitations imposed by acoustic recording dramatically impacted performance practice, requiring musicians to abandon artistic standards, conservatory and stage training, and even sacrifice the integrity of their instruments. Certain instruments had to be modified to project and reproduce convincingly amidst the harsh hiss of wax and shellac. Hammer felts were stripped from pianos and trumpet horns were attached to violins. Understandably, similar modifications weren’t as readily applied to 17th century harpsichords and violas da gamba. The harpsichord performed by Wanda Landowska on a 1923 recording of Handel’s The Harmonious Blacksmith is almost unrecognizable, a mere suggestion of the instrument. Compared to the harpsichord recorded over a decade later in the opening track Le pendant d'oreille by Antoine Dornel, which is by no means crystal clear, the Landowska recording’s limitations transform the harmonically rich harpsichord into an amorphous specter, morphing between organ, piano, and harpsichord. The higher frequencies afforded by electrical amplification allowed for more accurate reproduction of instrumental timbres and increased speech clarity. However, pre-World War II recording technology still could not reproduce even half the range of human hearing. Acoustic recording could not adequately capture delicate instruments like the clavichord, but even the clavichord performances featured on 2000 Years of Music sound thin and unfocused in the early electrical era, further smothered under intense surface noise.

The material of the media–the shellac, its wear, and its mediation–contributes significantly to the audible grain on these recordings and the perception of the media as aged. Between about 1896 and 1948, record discs were primarily made from shellac (a resin secreted by tree insects) mixed with fillers to aid against wear and to color the record.[17] These fillers are largely responsible for that frying pan sound so typical of early recordings. In addition to the frequency limitations already discussed, the surface noise contributes to unintelligibility by masking or overpowering frequency content of the instruments and drowning out particularly soft passages. It's noteworthy that different recordings in the mix have different flavors of surface noise, from overwhelmingly noisy to barely present, likely a result of how the records were digitally transferred and subsequently edited. Johann Pezel’s Gigue has almost no surface noise while Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in B-Flat swims in a haze of crackle. Different needles, different EQ settings, and different amounts of noise reduction all impact the resulting sound. Too much noise reduction and the sound becomes flat. Too much surface noise and the saturation makes it hard to listen to for an extended period. Although likely originally recorded mono in the 1920s and 1930s (commercial stereo recording was only introduced in the 1950s),[18] the transfers are almost all stereo files. Judging by the variations in surface noise between the channels, some of these tracks aren’t just dual mono but were instead converted to digital in stereo. The result is spatialized surface noise which, depending on preference, either adds a layer of depth to the frying pan sound or increases irritation.

The texture or grain of media, like Barthes’ grain of the voice, is the presence of the media’s material in performance conveyed through the physical and digital body of the recording.[19] The grain exists in both presence, like the hiss of tape and the crackle of vinyl, and in absence, like the flattening and data loss of .mp3 compression and streaming. When we listen to a record, we hear the history of that object perform in real time: the wear of the grooves, the scratches, the dust, the specific pressing. Even with a new, clean, well pressed vinyl record on a well-maintained player, the needle drop breaks the illusion that we’re listening only to the recording. Surface noise exists because the record exists, because it performs and is performed. It is both enacted and self-inflicted.

How we hear or don’t hear the texture of media varies depending on a person’s background and experience with recorded sound. Someone who grew up listening to records and cassettes, likely an older listener, may more easily hear past the surface noise, processing it instead as negative space. Listeners who grew up with the comparatively (and debatably) frictionless media of CDs, MP3s, and streaming more readily recognize record noise as something other and additional to the recording. They may respond first to the quality of the recording before commenting on its content. A very early acoustic recording reads as an historical sound object on an historical format which itself is often aged and decayed (e.g. the voice of one of the last castrati recorded over a century ago on a wax cylinder that has gathered dust for that same amount of time). Together the grain and content are heard as old and ethereal, out of time and place. Even if the recording is new, it can still sound “old.”

In a video from 2018 titled “Recording on 100-Year-Old Equipment,” popular YouTuber-guitarist Rob Scallon attempts to record acoustic guitar on a wax cylinder phonograph supposedly from “Edison’s New York studio.”[20] The humorless operator wearing a sport coat plays a few cylinders for Scallon who comments, “Sounds like we’re listening to ghosts.” The operator responds, “Well, we are,” true since everyone on the recording is most certainly dead. Perhaps this, hearing voices of the dead doubly preserved in wax and YouTube content, is the future Edison envisioned in 1878 when he described the phonographic goal of “indefinite multiplication and preservation of [captive] sounds, without regard to the existence or non-existence of the original source.”[21] The recording process only goes so well for our friend. Even after playing at the top of the instrument’s dynamic range directly into the horn, on playback the guitar barely cuts through the heavy layer crackle. Scallon appears disappointed by the results. He tries again, this time recording an “old timey tune” with vocals. It sounds mildly better, but mostly because the black and white video of him playing the song in a pair of overalls and a fake beard sells the act better.[22] The video ends with a message to the viewer coming right out of the phonograph, the traditional YouTuber call to action to “smash that like button” trapped within a limited frequency band and buried under noise. This is the texture of media: the sound of the material, the recording, the playback, the decay and wear, often the content, and the perception of another world within these sounds.

In addition to frequency range and noise, limited space on discs provided another unique challenge to the performers and producers in the early twentieth century. Cylinders and single-sided discs of the early 1900s could hold about two minutes of noisy, limited frequency range audio. From the late 1920s, play time per side doubled to a whopping four and a half minutes. The format demanded musicians arrange, abbreviate, and even compose to fit within these technical limitations. A 1923 recording of Chopin's Scherzo no. 1 in B minor lasts four and a half minutes; the 1926 release of the same piece on piano roll last eight of the fifteen total minutes available to the format.[23] Even in an abridged form, a 1903 release of Verdi's Ernani by the Italian branch of the Gramophone Company HMV spanned the length of forty single-sided discs. The twenty-four 10” sides of 2000 Years of Music totals only a little over an hour, each side rarely going over three minutes. In the accompanying textbook, Curt Sachs addresses the effect of time constraint on the interpretations but offers a fun way for the listener to contribute to the disc’s performance to achieve the intended artistic results: “It is advisable when playing this record to slightly retard the speed indicator of the gramophone (say to 76 revolutions). In order to record the whole movement on the usual three minute length disc, the players had to increase the Tempo. The customary 18th century pitch being lower than that of the present day, any idea of consequent loss of effect is counter acted.”[24] With so many necessary interventions and concessions, the performer, and too the listener, must creatively engage the technology to convey a coherent version of the work even if that means veering further from a “true” representation of the music.

J. A. Fuller Maitland, a student at Cambridge in the 1870s, describes the attitude towards early music in his studies as nearly always taken for granted "that there was no beauty such as could appeal to modern ears, so that the respect with which we were encouraged to approach them was purely due to their antiquity."[25] There's more to these recordings than an interest in the antique sound object. There's a lot of beauty, expressivity, risk, and fun. We can take this stopgap at the intersection of early music and recorded music history as creative input for the possibilities of early music experimentation as a listener, composer, or performer. Even if the results are inauthentic within the current field of historically informed interpretation, these recordings exhibit a technologically informed performance practice equally evolving and malleable as the content recorded. This is not a case against the pursuit of authenticity or recreation of historical music in the form originally heard. Although abbreviated, noisy, and at times garish, mass audiences in the twentieth century first heard this repertoire through mechanical reproduction. Early recording produced its own unique and authentic form of early music.

Preference for “late” over “early” in terms of technology, interpretation, scholarship, and performance practice would place much of the recorded music featured in this mix into the dustbin, only to be retrieved for novelty and study, never listening. Virtuosic listeners and audiophiles demand high quality recordings by extraordinarily skilled and specialized musicians. For music filled with idiosyncrasies, there's often little room for accepted experimentation other than by rule-breaking amateurs and composers. On these recordings, in varying quality and amidst layers of crackle, we hear experimentation in folds. From the original recordings made nearly a century ago to the MP3s now streaming through the internet, the extensive technological mediation produces an audible chasm between manuscript and digital file. Vibrato and crackle, verging on sacrilege, fill the negative space that gives contemporary recordings their magnificence and sterility. This mix presents artifacts and distortions, speculative histories of performance practice, musical decisions to puzzle over and laugh at, and compelling moments of experimentation that exhibit form in progress.

[1] Helewyse de Birkestad, “When is pizza not a pizza?,” Medieval Cookery, April 14, 2004, <https://www.medievalcookery.com/helewyse/pizza.html>.

[2] Thomas Forrest Kelley, Early Music: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 2.

[3] Timothy Day, A Century of Recorded Music: Listening to Musical History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 80.

[4] Pierre F. Roberge, “L’Anthologie sonore,” Medieval.org, <http://www.medieval.org/emfaq/cds/ans99999.htm>.

[5] Curt Sachs, “Two Thousand Years of Music: A Concise History of the Development of Music from the Earliest Times down to the End of the Eighteenth Century,” trans. Mark Lubbock in 2000 Jahre Musik auf der Schallplatte: Alte Musik anno 1930, ed. Pekka Gronow, Christiane Hofer, and Frank Wonneberg (Vienna: Gesellschaft für Historische Tonträger, 2018), 157.

[6] Harvey Grace, “Musical History by Gramphone” in 2000 Jahre Musik auf der Schallplatte: Alte Musik anno 1930, ed. Pekka Gronow, Christiane Hofer, and Frank Wonneberg (Vienna: Gesellschaft für Historische Tonträger, 2018), 209. Originally published in The Musical Times (February 1, 1932), 133-5.

[7] Timothy D. Taylor, “Sound Recording Introduction” in Music, Sound, And Technology in America: A Documentary History of Early Phonograph, Cinema, and Radio, ed. Timothy D. Taylor, Mark Katz, and Tony Grejada (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 12.

[8] Day, A Century of Recorded Music, 16.

[9] Ibid., 7.

[10] Richard Koszarski, “On the Record: Seeing and Hearing the Vitaphone,” in The Dawn of Sound, ed. Mary Lea Bandy (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1989), 18.

[11] John C. Steinberg, "The Quality of Speech and Music," Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 12, no. 35 (September 1928), 641. doi: 10.5594/J13125.

[12] Thomas A. Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” in Music, Sound, And Technology in America: A Documentary History of Early Phonograph, Cinema, and Radio, ed. Timothy D. Taylor, Mark Katz, and Tony Grejada (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 31. Originally published in North American Review 126 (1878), 530-36.

[13] David L. Morton Jr., Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004), 45.

[14] Ibid., 46.

[15] Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” 34.

[16] Ibid., 35.

[17] Morton, Sound Recording, 38.

[18] Ibid., 95.

[19] Roland Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image, Music, Text trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995): 188. “The ‘grain’ is the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs.”

[20] Rob Scallon, “Recording on 100-Year-Old Equipment,” YouTube video, January 15, 2018, https://youtu.be/1n2b0NdL6_E.

[21] Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” 32.

[22] RobScallon2, “My Uncle the Philanthropist - Mr. Wibblespoon (recording into wax),” YouTube video, January 18, 2018, https://youtu.be/TBpQR2z2eko.

[23] Day, A Century of Recorded Music, 7.

[24] Curt Sachs, “Two Thousand Years of Music,” 159.

[25] Brian Blood, "The Dolmetsch Story," Dolmetsch online, modified January 6, 2022. https://www.dolmetsch.com/Dolworks.htm.

Dates, titles, credits, and other information for the track listing were compiled from Medieval.org and Archive.org.