SEMIBEGUN 001: EARLY RECORDINGS OF EARLY MUSIC 1928 - 1939

Air/Release Date: June 8, 2022

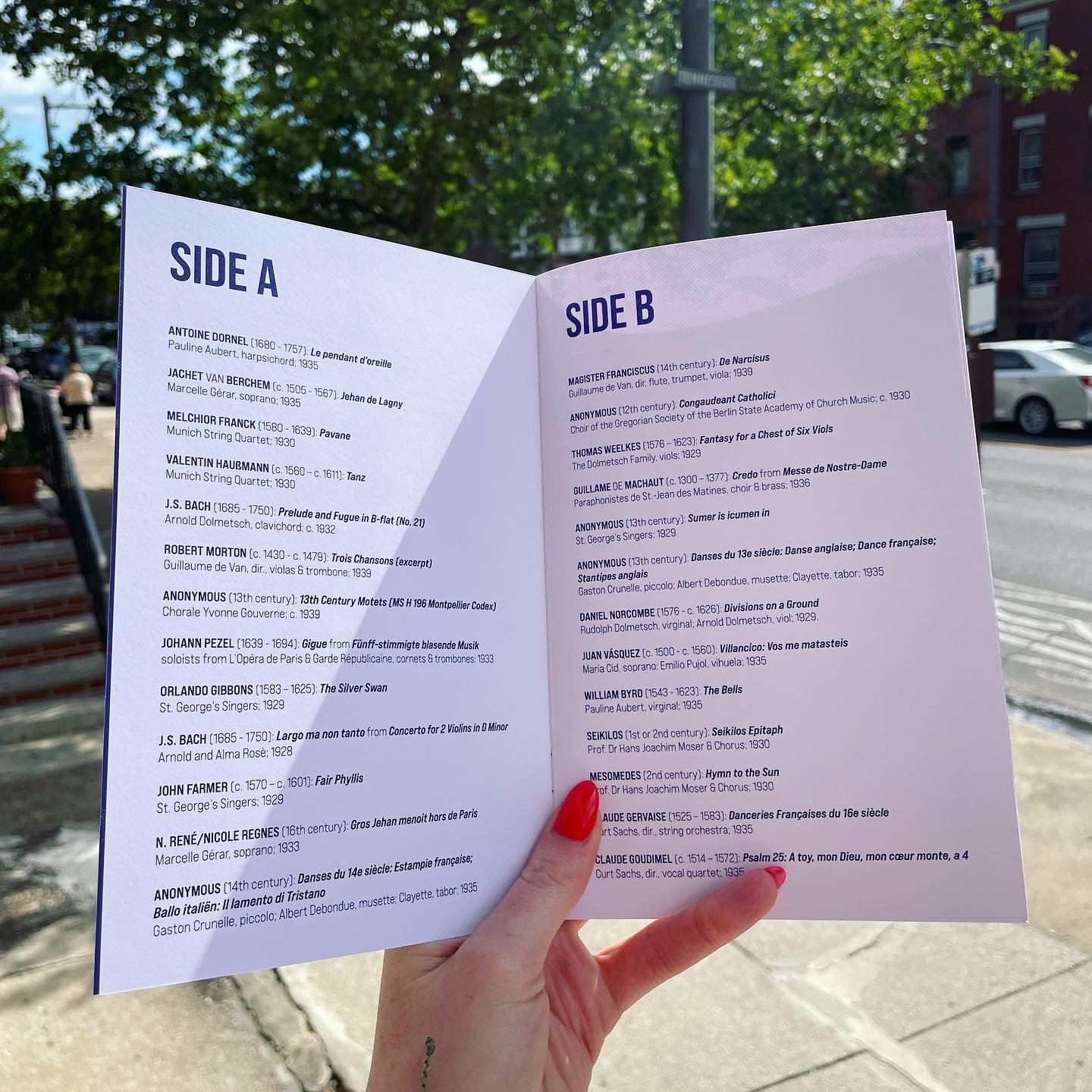

A

Antoine Dornel (1680 - 1757): Le pendant d'oreille

Pauline Aubert, harpsichord; 1935Jachet van Berchem (c. 1505 - 1567): Jehan de Lagny

Marcelle Gérar, soprano; 1935Melchior Franck (1580 - 1639): Pavane

Munich String Quartet; 1930Valentin Haußmann (c. 1560 – c. 1611): Tanz

Munich String Quartet; 1930J.S. Bach (1685 - 1750): Prelude and Fugue in B-flat (No. 21)

Arnold Dolmetsch, clavichord; c. 1932Robert Morton (c. 1430 - c. 1479): Trois Chansons (excerpt)

Guillaume de Van, dir., violas & trombone; 1939Anonymous (13th century): 13th Century Motets, MS H 196 Montpellier

Chorale Yvonne Gouverne; c. 1939Johann Pezel (1639 - 1694): Gigue from Fünff-stimmigte blasende Musik

soloists from L'Opéra de Paris & Garde Républicaine, cornets & trombones; 1933Orlando Gibbons (1583 – 1625): The Silver Swan

St. George's Singers; 1929J.S. Bach: II. Largo ma non tanto from Concerto for 2 Violins in D Minor

Arnold and Alma Rosè; 1928John Farmer (c. 1570 – c. 1601): Fair Phyllis

St. George's Singers; 1929N. René/Nicole Regnes (16th century): Gros Jehan menoit hors de Paris

Marcelle Gérar (soprano); 1933Anonymous (14th century): Danses du 14e siècle: Estampie française; Ballo italiën: Il lamento di Tristano

Gaston Crunelle, piccolo; Albert Debondue, musette; Clayette, tabor; 1935

B

Magister Franciscus (14th century): De Narcisus

Guillaume de Van, dir., flute, trumpet, viola; 1939Anonymous (12th century): Congaudeant Catholici

Choir of the Gregorian Society of the Berlin State Academy of Church and School Music; c. 1930Thomas Weelkes (1576 – 1623): Fantasy for a Chest of Six Viols

The Dolmetsch Family, viols; 1929Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300 – 1377): Credo from Messe de Nostre-Dame

Paraphonistes de St.-Jean des Matines, choir & brass; 1936Anonymous (13th century): Sumer is icumen in

St. George's Singers; 1929Anonymous (13th century): Danses du 13e siècle: Danse anglaise; Dance française; Stantipes anglais

Gaston Crunelle, piccolo; Albert Debondue, musette; Clayette, tabor; 1935Daniel Norcombe (1576 - c. 1626): Divisions on a Ground

Rudolph Dolmetsch, virginal; Arnold Dolmetsch, viol; 1929.Juan Vásquez (c. 1500 - c. 1560): Villancico: Vos me matasteis

Maria Cid, soprano; Emilio Pujol, vihuela; 1935William Byrd (1543 - 1623): The Bells

Pauline Aubert, virginal; 1935Seikilos (1st or 2nd century): Seikilos Epitaph (Skolion of Seikilos)

Prof. Dr Hans Joachim Moser & Chorus; 1930Mesomedes (2nd century): Hymn to the Sun

Prof. Dr Hans Joachim Moser & Chorus; 1930Claude Gervaise (1525 – 1583): Allemande (Danceries Françaises du 16e siècle)

Curt Sachs, dir., string orchestra; 1935Claude Goudimel (c. 1514 – 1572): Psalm 25, A toy, mon Dieu, mon cœur monte, a 4

Curt Sachs, dir., vocal quartet; 1935

Cassette + booklet available for purchase, please email.

When considering a now well established object’s earliest form — for instance, the slow, multiton computers of the 1940s — one is tempted to identify differences between then and now as faults that have been remedied through years of improvement. This interpretation is often reasonable, especially when observing how a calculator that once filled an entire room now fits in a pocket. If today you were served the rose and nut flavored cake that passed as pizza in Renaissance Italy,¹ the proper reception would be “thank god we’ve come such a long way.” But even if most wouldn’t recognize the dish as pizza, the peculiar culinary experience expands upon what is customarily accepted as such.

Similarly, pre-World War II recordings of early music are more than mere signposts of how far the technology has come. Although surface noise and limited frequency range can easily push the musical content into the background, the performances on these records extend beyond the curiosity of the antique object. Beyond the noise of historical recording and reproduction, the listener confronts unconventional and dated interpretations. Developments in the decades following the war contributed to the "accuracy" of historically informed music practice while technological advancements minimized the presence of the medium. However, the stunning performances of renaissance vocal music offered in excessively high definition available today should not render this history of recorded music obsolete.

The period of "early music" that commonly comprises the European Middle Ages to the Baroque era (and sometimes includes ancient music) covers greatly varying styles across centuries, composers, cultures, religions, and purposes. In other words, early music consists of myriad early musics. Similar in spirit to much twentieth and twenty-first century concert music, the distinctiveness of early music may seem convention-defying to the cultivated classical listener: angular form, metrical ambiguity, and expectation-thwarting harmonic movement. The dated idea that the musical developments between 9th century organum and common practice classical tonality establish a history of linear progress reduces the musics' aesthetic value to mere stepping stones toward late Romanticism. The dominance of “late” over “early” in terms of technology, interpretation, scholarship, and performance practice would place much of the recorded music featured in this mix into the dustbin, only to be retrieved for novelty and study, never listening. Virtuosic listeners and audiophiles demand high quality recordings, and within the niche world of early music performance, more than a century’s worth of scholarship has set the standards that extraordinarily skilled and specialized practitioners maintain. For music filled with idiosyncrasies, there's often little room for accepted experimentation other than by rule-breaking amateurs and composers. On these recordings, in varying quality and amidst layers of crackle, we hear experimentation in folds.

This mix contains music recorded between 1928 and 1939, spanning Ancient Greek to Baroque periods.² Here, different ideas of “early” intermingle with one another: early music, early recording technology, and early historical performance practice. All of the tunes were transferred from 78-rpm shellac discs by a variety of sources on Internet Archive. Anyone who has taken a survey course on Western classical will likely recognize music history textbook staples like Sumer is icumen in and Seikilos Epitaph — two fantastic vocal pieces — but some deeper cuts emerge as well. The earliest works date to the first few centuries of the common era, and the latest almost hug the beginning of the Classical period.

The majority of the selections come from three anthologies of historical music: Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye, L’Anthologie Sonore, and Parlophone’s 2000 Years of Music. The music directors of these records, some of whom were musicologists responsible for rediscovering repertoire and developing its performance practice, presented authoritative performances for the time.³ The Dolmetsch family, featured on many of the Columbia recordings, performed on clavichord, virginal, harpsichord, and viols when piano and modern strings would have been considered acceptable substitutions. However, the heavily affected performance of Danceries Françaises du 16e siècle with string orchestra indicates this attention to instrumentation was not always given or perhaps not yet available. Entirely absent in these recordings is the now ubiquitous practice of straight tone, or singing without vibrato. St. George’s Singers consistently vibrate throughout the two famous English madrigals Fair Phyllis and The Silver Swan. This tendency is not restricted to the voice: the string quartet’s punchiness doused in heavy vibrato on Melchior Franck’s Pavane more appropriately suits a contemporary Fritz Kreisler performance than a dance from the early 1600s. Sharing a similar level of outmoded intensity, the ensemble performing Guillaume de Machaut’s beautiful 14th century Messe de Nostre-Dame belt in a style not unlike American shape note singing. Today, such performances would more likely be heard in student and amateur ensembles than on professional releases.

Some of the more curious performances come from the label L’Oiseau Lyre, a passion project led by socialite Louise Hanson-Dyer that began producing records in 1938. Alongside a crew of young and seasoned scholars, she recorded editions from the label’s publishing arm Éditions de l’Oiseau-Lyre, including selections from the 13th-century Montpellier Codex. The motet from this codex of medieval polyphony features delicate high voices employing narrow vibrato and, perhaps most interestingly, the interjection of an unedited reference pitch given by a piano during a brief pause at around the two-third mark. The far more clumsy performance of Magister Franciscus’s De Narcisus by a jarringly out-of-tune and inspiringly lifeless ensemble of flute, viola, and trombone paints a certain rugged early twentieth century approach to period performance. For even the uninitiated listener, the decision to cut something like this to tape seems questionable. This was not always a matter of historically uninformed direction, however. The recording and reproduction technology imposed other difficulties in the process of capturing this music.

The starting year of this mix’s range, 1928, roughly corresponds to a significant point in the history of recording. Electrically amplified recording replaced acoustic in 1925, which impacted both ease and quality of recording.⁴ The flexibility afforded by an electrically amplified microphone system could capture sounds around a wide area, which ended the practice of hellishly cramped recording sessions around an acoustic horn. This led to more comfortable working conditions and an expansion of how and what music ensembles could practically record. Increases in captured frequency range also expanded this practicality. Acoustic recording could only reproduce sound within a frequency range of 168 to 2,000 Hz (the human ear can hear, ideally, between 20 and 20,000 Hz).⁵ This limitation accounts for the lack of speech intelligibility on wax cylinder recordings. Important timbral information that helps us differentiate vowels and consonants is just entirely absent. The jump to electrical amplification in the mid 1920s increased the captured frequency range to 5,000 Hz (down to 100 Hz on the lower end), and again up to 8,000 Hz by 1934. In the acoustic recording era, certain instruments had to be modified to project and reproduce convincingly amidst the harsh hiss of wax and shellac. Hammer felts were stripped from pianos and trumpet horns were attached to violins. The higher frequencies afforded by electrical amplification allowed for more accurate reproduction of instrumental timbres and increased speech clarity. However, pre-World War II recording technology still could not reproduce even half the range of human hearing. This primarily gives these recordings that characteristic “old” sound.

The material of the media also contributes to the particular sound of old recordings. Between about 1896 and 1948, record discs were primarily made from shellac (a resin secreted by tree insects) mixed with fillers to aid against wear and to color the record.⁶ These fillers are largely responsible for that frying pan sound so typical of early recordings. It's noteworthy that different recordings in the mix have different flavors of surface noise, from overwhelmingly noisy to barely present, likely a result of how the records were digitally transferred and subsequently edited. Johann Pezel’s Gigue has almost no surface noise while Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in B-Flat swims in a haze of crackle. Different needles, different EQ settings, and different amounts of noise reduction all impact the resulting sound. Although they were likely recorded mono in the 1920s and 1930s (commercial stereo recording was only introduced in the 1950s), the transfers are almost all stereo files.⁷ Judging by the variations in surface noise between the channels, some of these tracks aren’t just dual mono but were actually converted to digital in stereo.

From the original recordings made nearly a century ago to the MP3s downloaded from the internet and the final transfer to tape, the extensive technological mediation produces the audible chasm between manuscript and cassette tape. Vibrato and crackle, verging on sacrilege, fill the negative space that gives contemporary recordings their magnificence and sterility. This mix presents artifacts and distortions, speculative histories of performance practice, musical decisions to puzzle over and laugh at, and compelling moments of experimentation that exhibit form in progress.

1. “A Philosophy of Pizza Napoletanismo (Part 6: Fragments of History of Neapolitan Pizza),” Pizza Napoletanismo, <https://pizzanapoletanismo.wordpress.com/2012/05/11/a-philosophy-of-pizza-napoletanismo-part-6-fragments-of-history-of-neapolitan-pizza/>.

2. Dates, titles, credits, and other information for the track listing have been compiled from Medieval.org and Archive.org.

3. Timothy Day, A Century of Recorded Music: Listening to Musical History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 80.

4. Ibid., 16.

5. Ibid., 7.

6. David L. Morton Jr., Sound Recording: The Life Story of a Technology (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004), 38.

7. Ibid., 95.